SMALL CRAFT ADVISOR interview

2020

Seascape

The Webb Chiles Interview

W e caught up with famed sailor and author Webb Chiles just after he’d finished his sixth circumnavigation at age 77. Webb’s long list of exploits are well known,

including his harrowing Pacfiic crossing aboard an open 19-foot Drascombe Lugger called Chidiock Tichborne. There might not be anyone alive with as many small-boat sea miles and stories as Chiles—so naturally we had plenty of questions for him.—Eds

When did it all start—your love of boats and sailing and then especially the thirst for adventure?

First, I do not love boats, as some seem to, and I do not thirst for adventure.

I have great admiration for some boats, particularly small ones that if well designed, well built and well sailed can do so much more than most think possible, but I do not love them.Long ago I learned not to love anything or anyone who could not love me back, and while I believe that boats, along with musical instru- ments made of wood, seem more alive than any other of man’s creations, they are not.

Of adventure, I have said that amateurs seek adventures, pro- fessionals seek to avoid them. I have lived this long and sailed so

far only because I plan, prepare to the extent of my resources, never do anything at the last minute, and though I have taken risks, I have never taken an uncalculated risk.

Having said that, my desire to sail oceans came from my childhood spent in a suburb of Saint Louis, Missouri, about as far from the ocean as one can be. I was an only child and not close to my mother and stepfather and I did not want to be there. So I escaped as many do through books. I read Slocum and Conrad and Irving Johnson’s articles in National Geographic about his circumnavigating with paying crew in the brigantine Yankee.

In my early teens my grandmother, my father’s mother, and her last husband, whom I thought of as my grandfather, retired to a small cottage two buildings in from the ocean at San Diego’s Mission Beach. I spent my high school summers with them. That probably saved my life. I was over the sea wall and on the beach or in the ocean almost all day every day. I saw sailboats pass. No one in my family had ever sailed. No one I knew sailed or had a boat. I told myself that one day I would do that, and obviously I have.

Were you prone to risk-taking when you were young?

See above. I am not prone to risk-taking now and never have been. I do all I can to minimize risk, knowing that it cannot totally be eliminated.

Did your father and grandfathers dying so young leave you with a sense of urgency to experience everything you could quickly?

Yes. I never knew my father. He and my mother separated before I was born, but his suicide when I was seven years old made death real to me young, as did the knowledge as I grew up that both my grandfathers had died young, though not of

causes that were likely to affect me. Still I never expected to have much time. Yet I have now more than doubled their lives.

You say you’re not prone to risk-taking. How then do you characterize—in terms of the relative risk—something like your latest circumnavigation? Aren’t you knowingly doing something dangerous or daring, or do you feel like you’re so prepared that it’s mundane or at least relatively safe?

I knowingly do things that are dangerous. I have never thought of “daring” and don’t consider myself brave. I have written that courage is doing something that you are afraid to do. I

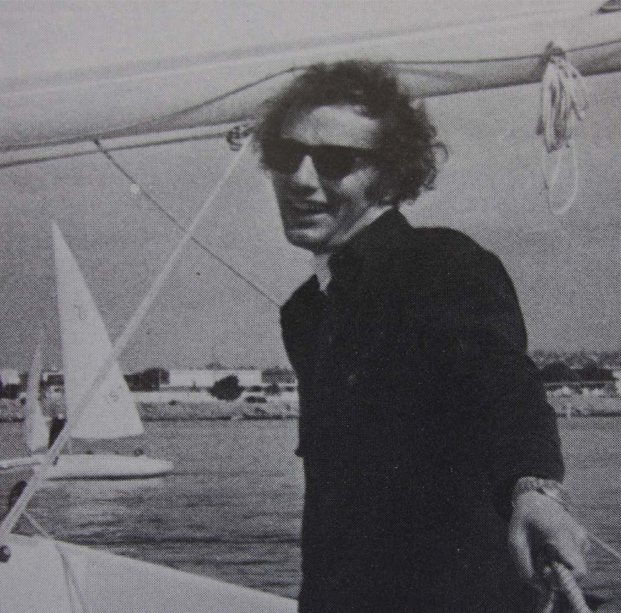

L TO R: November 2, 1974, leaving for Cape Horn. Sailing Chidiock Tichborne. All smiles during latest circumnavigation aboard Moore 24 Gannet.

don’t do things I am afraid to do. People sometimes think I’m brave because I do things they are afraid to do. What I do believe I have is nerve, and nerve is after planning and making the best preparation your resources permit the willingness to embark on an endeavor whose outcome is uncertain and may be fatal.

Of my circumnavigation in Gannet, I do not think it mun- dane. It was hard. I do hard. And I always thought it was as safe as circumnavigating in a bigger boat. Gannet, a Moore 24, is a great boat that meets my criterion of being well-designed and well-built, and I like to think well-sailed.

Some years ago when you were asked about what sailing means to you, you said “freedom.” What are the aspects of land-life that you most want freedom from?

The evening news. Also the ugly clutter of cities where beauty can only be found in tiny oases and silence never, and the stupid- ity and self-serving greed for power of politicians.

But I also sail oceans not just to escape land negatives but to experience ocean positives, to enter what I have called the monastery of the sea. In mid-ocean there is simplicity, purity and beauty. There is no ugliness. There are only natural sounds other than the music I choose to listen to. An ocean passage is

“I don’t do things I am afraid to do.

People sometimes think I’m brave because I do things they are afraid to do.”

not ambiguous as is much of modern life. There is complete and clear-cut responsibility for yourself. You start a passage and you either reach the port you sailed for or you don’t. It is wonderful out there.

Do you ever suffer from loneliness on your voyages?

I have been married many times. Now for 25 years to Carol. That we met at the only brief period in our lives that we could have come together is the great grace of my life. I miss her, but no, I am not lonely at sea. As I have said, I was an only child and it took.

Assuming every life decision comes with trade offs, what are the most significant things you’ve given up in exchange for your life of adventure?

I deliberately never had children, knowing negatively from my own childhood that parents owe their children a lot for a long time. I have ever since my own childhood wanted to live the life I have and I did not think I could do that and be a good parent. However, not having children has not been a sacrifice for me.

I have lived the life I wanted. I have made voyages no one else has or had even imagined. I have put some words together. And I have loved and been loved by some of the most intelligent, charming, beautiful women of two generations.

Why do you think so few people—who presumably seek or appreciate freedom as well—are able to actually cast off the dock lines?

You are asking me to speak for others. You would have to ask them.

Is crossing an ocean on a small boat more or less difficult than most people think?

Probably both. People say that I make it look easy. Well, I write with a smile, the great ones do. Let others set off around the world in a Drascombe Lugger or a Moore 24 with no way to call for help if they get in trouble, and then ask them.

How about small boats themselves—can they be as seaworthy as larger boats, or is the small-boat sailor almost always at some disadvantage?

I have owned three great boats and two of them were small, Chidiock Tichborne, an undecked 18-foot Drascombe Lugger, and Gannet, an ultra-light Moore 24. My other great boat was Resurgam, a 36-foot S&S design of a class known as She 36s built in England. The best small boats are every bit as seaworthy as any larger.

We love your famous quote “A sailor is an artist whose medium is the wind.” We appreciate the quote in its more literal sense, as sailing has always felt as much like an art as a science to us, but presumably you also see real artistic expression in your sailing as well? That’s not something you hear a lot of people talk about. In fact the only other person we can immediately

recall talking this way is the Dutch artist Bas Jan Adler, who set off across the Atlantic in 1975 in his 13-foot Guppy as part of an art piece and was never heard from again. Tell us about sailing as an artist.

While most think of me as a sailor, I think of myself as an artist and have defined the artist’s fundamental responsibility as going to the edge of human experience and sending back reports. That is what I have done for almost half a century. I am as much a writer as a sailor and care about my words as much as my voyages.

We like where you wrote: “The sea is not cruel or merci- less. The sea is insensate and indifferent.” You’re right, of course, and the ocean doesn’t need to be anthropomor- phized to be a wild and dangerous place. But you must have found yourself in conditions and situations where it felt like the ocean or Mother Nature had it out for you—where it felt like there was a sense of the malevolent?

I think that a few times in Storm Passage, about my first circumnavigation which was two stops in what was then world-record time for a solo circumnavigation in a mono- hull, and during which I became the first American to sail alone around Cape Horn, I fell into the pathetic fallacy, but I wrote even then that the sense that a storm front perhaps a thousand miles long was directed specifically at me was false. I think there is survival value in recognizing that and being tough-minded.

I do not believe in Mother Nature, either.

What was you single worst or scariest moment on the wa- ter? What happened?

I have been in so many survival situations over more than four decades that I no longer remember some of them. I once wrote that almost dying is a hard way to make a living.

I have been in Force 12 at sea at least eight times. I have put the mastheads of four boats in the water, which is a club you probably don’t want to join. Any time that happens, the animal within is afraid.

Of survival situations, when Chidiock Tichborne hit some- thing, probably a container, in the South Pacific between Fiji and what is now Vanuatu and I was thrown from sleeping into the ocean, then to drift for two weeks in an inflatable before reaching land on my own, was probably the most extreme.

During Gannet’s circumnavigation, we were in two 55-knot gales, but the most dangerous moment came just after noon on a day of pleasant sailing a few hundred miles north of Apia, Samoa. I was standing in the companionway when I saw two waves 10 feet high and close together coming toward us at an angle to the other waves which were only 3 and 4 feet. The first hit us and knocked Gannet onto her beam. The second only an instant behind held us there. I ducked into the cabin and slid the companionway shut but could not reach the vertical slat. I was bracing myself looking down into the ocean. The lee rail was under water and the ocean only inches from reaching the cockpit. If it had we would have gone under. I felt nothing. I merely watched to see if the little boat would

right herself before the ocean flowed in. She did.

You wrote that in each of your circumnavigations you sought a new experience, that “I did not want to be like an old rock star forever singing the songs of his youth. I wanted to sing a new song.” Reflecting now, how would you rate the boats in terms of their fitness for the purpose?

Probably the least fit boat was Egregious, the engineless Ericson 37 in which I made my first circumnavigation. But she was the best I could afford at the time and present-day readers must try to remember that in 1975 Cape Horn was still an almost unknown frontier. I am not only the first American to round it alone, I am as far as I know the first even to try. So no one in this country, and only a handful in the world, knew then what it is like to be in the Southern Ocean for months and more than 10,000 miles. Not many know now.

All my other boats have been suitable for my purposes.

Did your general voyaging strategy change dramatically depending on the boat you were aboard?

Naturally one sails an 18-foot open boat differently than a 37-foot one with a deck. Chidiock Tichborne had 12 inches of freeboard. Gannet has 24. But essentially I sail all boats pretty much the same. I try not to heel more than 20o, though sometimes on Gannet that is difficult to achieve. My experience is that boats go faster when heeled less than 20o and life on board is certainly easier.

Any thoughts on small boat handling in heavy weather— either some of your own strategies or where you see others get in trouble?

ABOVE: Webb at the helm of Chidiock Tichborne.

Chidiock Tichborne was a yawl. I think a yawl rig has great safety advantages on small, open boats. You can lower the main completely and sail under jib and mizzen. Also she hove-to better than any of my other boats which were sloops and one cutter. Furl her jib. Lower the main. Put the centerboard three- fourths down. Tie the tiller amidships. Flatten the mizzen and it weathercocked the bow right into the wind.

Generally in heavy weather, assuming sea room, which I usually had, I would head off down wind in extreme conditions under bare poles letting the wind vane self-steering device on those of my boats that had one steer as long as it could. When waves began to overwhelm it, I simply lay ahull.

Gannet is the first boat on which I’ve carried a Jordan drogue. Fortunately I never had to deploy it. I did not consider the 55-knot gales survival storms. In the first off New Zealand I hand steered under a scrap of jib to reach port before the wind headed us. In the second off Durban, South Africa, I lay ahull for 36 hours.

Obviously you are content to live simply, and we know you voyage without sponsors, shore teams, etc., but we understand you have a soft spot for electronics aboard? What do you con- sider worth carrying?

I am not sure about a soft spot for electronics.

Gannet has a depthsounder. During parts of her circumnavi-

gation she also had RayMarine solar-powered wind instruments, but Gannet’s masthead went in the water three times and, under- standably, masthead wind instruments are not built for that. I replaced the Windex and masthead wind in New Zealand and again in South Africa. The masthead went in the water a third time in a gale off Namibia. I replaced the Windex a third time

in Saint Lucia, but not the wind. I haven’t decided yet whether I ever will.

I use a mast-mounted Velocitek ProStart to read out COG and SOG when on deck.

I have a handheld VHF which is useful to talk to officials when entering port and occasionally for calling shore launches in places such as the Balboa Yacht Club in Panama where you are not allowed to go ashore in your own dinghy.

I have a Yellowbrick tracking device. Initially this was intended to enable Carol to see where I was, but others have enjoying view- ing the track and I like seeing it myself after I reach port. I like it because all I have to do is turn it on, set the interval I want it to upload our position, and forget it. I set the interval at six hours.

I have tiller pilots. Usually four or more on Gannet.

I had originally planned to put a self-steering vane on the boat, but being an ultra-light her transom is so thin it would have to be re-enforced for a vane. The quote I got from a boat yard for doing this was $5,000, more than half of the $9,000 I paid for Gannet. I decided I could buy a lot of tiller pilots for that. And I knew that I could use sheet to tiller self-steering as I have on other boats. For about half of Gannet’s 30,000-mile voyage she was steered by sheet to tiller.

I am a reader and I have a Kindle. Chidiock Tichborne and

Gannet are the only two boats I’ve owned on which I did not immediately build bookshelves. It is wonderful to have more than four hundred books with me in an object smaller than a single paperback.

I like music and have two UE Boom 2 Bluetooth speak- ers. They are waterproof, rugged, have unexpectedly good sound and can be set to play in stereo.

Music is streamed to those speakers by the most important electronic device on Gannet: my iPhone 7 Plus which holds about 700 albums of music and is also my primary chartplotter with world charts and the iNavX app. I also have the iSailor app, but found that the charts needed for Gannet’s voyage cost several hundred dollars more from iSailor than iNavX.

I also have the charts and apps in an old iPad mini and a new iPad Pro, which with a keyboard has become my primary computer.

During her voyage I used a 12-inch MacBook and had C-Map 93 charts in it. I could use a Garmin eTrex as GPS input, but never had reason to do so.

I am among the last to have had to navigate with a sextant. That was the only way to navigate during my first two circumnav- igations. I have a sextant on Gannet, but I have not taken a serious sight in more than 20 years. I do think it is probably a good idea for anyone sailing offshore at least to know how to take a noon sight for latitude which is quite easy.

And last, I recently upgraded my Apple Watch to a Series 5. This has its own GPS chip and a compass function. I have tested the compass underway and it is accurate. That function also enables me to read out latitude and longitude. I can now navigate by wrist.

I should mention that Gannet is totally self-contained. She has never been connected to shore power. She operates on wind, solar and my aging muscles.

Four 50-watt Solbian solar panels on deck charge two Group 24 AGM batteries which charge everything else, in- cluding the battery on our Torqeedo electric outboard which I only use the last mile or less entering harbors.

You must have great admiration for Chidiock Tichborne, your Drascombe Lugger. Recalling the worst of it you wrote, “If anything, in the 13 days since the pitchpole, I had come to have unlimited confidence in her. The sea could strip everything movable from her, toss her around like a toy, fill her with water, and she would patiently survive.” How about the Moore 24? What do you think of this design in some hindsight ?

As I have said, the Moore 24 is a great boat. A great design that is still winning races after more than 40 years. A great and honorable builder. I have met Ron Moore since completing the voyage. He and I both had no doubts that Gannet could make it.

I even love living in the restricted space of what I like to

call The Great Cabin. The biggest boats I have owned were 37-feet and I have said that if something won’t fit on a 37-foot boat, I don’t need to own it. Well, I can fit everything I need to live with in some style and grace on Gannet. I can write. I can read. I can listen to music. I can sail. I can drink 10-year-old Laphroaig from a crystal glass. That’s everything except Carol and she doesn’t want to fit on Gannet anyway.

What is the worst boat you’ve every owned or sailed?

I have almost never sailed with anyone except the woman in my life and almost never on other people’s boats.

The least good boat I have owned was my first, an Excalibur 26. She was not a bad boat and she sailed well enough, but she was not built to cross oceans, which was not her purpose.

It is to Ron Moore’s credit that Gannet was not built to cross oceans, either, but she could and did.

Any other small production boats you’re especially fond of ?

As I have said, I have not sailed on many boats. I have friends who own Welsford Pathfinders. Two were home built. They are similar to Drascombe Luggers, so much so that one friend is always being told by strangers that his boat is a Drascombe. I like them.

Of the countless places you’ve arrived at under sail, which are your favorite ports, harbors or anchorages?

This is easy. Anyone who reads my online journal knows that my favorite place in the world to have a boat is New Zealand’s

“I have written that the ocean does not give senior discounts and if it did I would refuse one..”

Bay of Islands. I would live there permanently if I could. The people are friendly. As an American I almost speak the language. The climate is moderate, never freezing in winter, seldom reaching 80o in the summer. And from the mooring I once owned off Opua, I could reach countless good anchor- ages on uninhabited islands in a few hours.

As far as being at sea, has the world changed much in the years you’ve been out at sea?

This is only anecdotal, but I see fewer birds and fish than I did on my first voyages.

Except in the Mediterranean and one afternoon off Costa Rica’s Cocos Island, perhaps surprisingly I have not seen a huge increase in plastic, but most of my sailing has been in the Southern Hemisphere and most of our species and most of the world’s problems are in the Northern.

What are you up to next?

I don’t know. Maybe nothing. I don’t mean to be unkind, but Carol and I smile whenever that question is asked, and it rou- tinely is, because it betrays a lack of understanding of Gannet’s voyage. It is the equivalent of asking someone who has just runanultramarathonaminuteafterhebreaksthetape,“Well, what are you going to do next?”

I don’t believe this is a function of my age. I have written that the ocean does not give senior discounts and if it did I would refuse one. Though frayed by time, I am a healthy old man who still uses his body hard and can and do my age in push-ups and crunches several times a week.

When I completed my first circumnavigation I was 35 years old and it was a year before I started to contemplate what be- came my open-boat voyage.

ABOVE: Adjusting the self-steering on the Moore 24 Gannet.

I have lived the life I wanted to live and I have understood it as I did so. I called the first part “Longing.” It ran from birth to 11:00 a.m. on Saturday, November 2, 1974, when I pushed the engineless Egregious away from her slip at Harbor Island Marina in San Diego for my first attempt at Cape Horn.

The second part which I have called “Being” ran from that moment until about 8:00 a.m. on Monday, April 29, 2019, when I tied up at the Customs Dock at San Diego’s Shelter Island, com- pleting Gannet’s voyage and my sixth circumnavigation.

I am still figuring out the third part.

I recorded two videos on the last full day of the voyage, titled The End of Being which might be of interest. There are two be- cause the battery died on my first camera.

www.youtube.com/watch?v=IU-IbkwZFdY www.youtube.com/watch?v=o9UILrfAk9s

Can you give our readers your website info and any other related links?

My main website is: www.inthepresentsea.com

My online journal is: www.self-portraitinthepresentseajournal. blogspot.com

My YouTube channel is: www.youtube.com/channel/UCdl7d- ZLxNI4VIB_eOiaNgiQ

My books can be bought from Amazon. Most are available in Kindle editions. Some can be downloaded for free from my web- site. Naturally I would prefer those who can afford to buy, do so.

I wish all of you sailing joy.